Canton POS

Celebrating Women: Dynamic Artists from the CMA Collection (Special Digital Exhibition)

In celebration of Women's History Month, the CMA has created this special digital exhibition highlighting some of the talented female artists in our Collection.

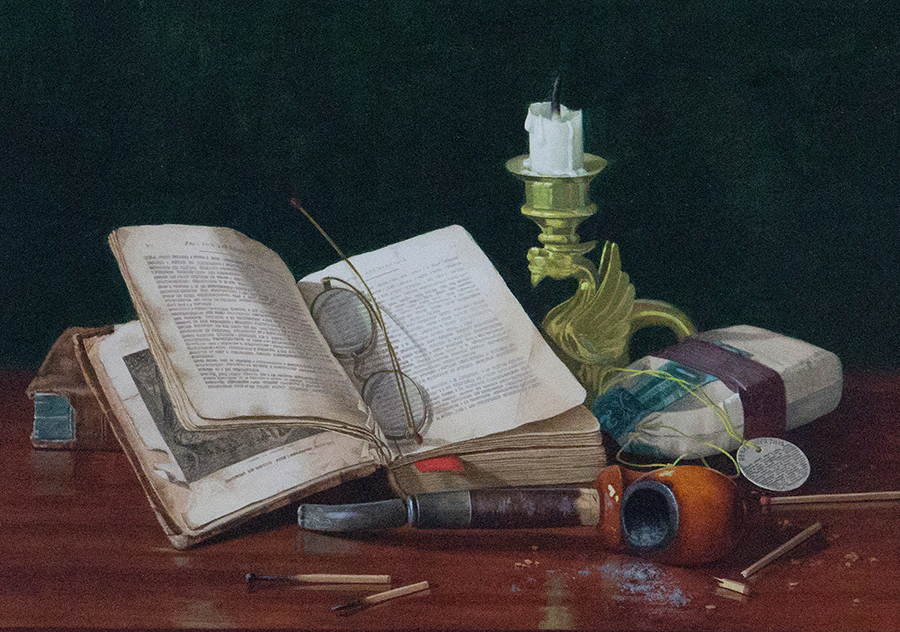

Claude Raguet Hirst

Ohio artist Claudine Raguet Hirst submitted her artwork under the name Claude R. Hirst in order to conceal her femininity and be taken seriously in a male-dominated art world. She was the only woman of her era to gain acclaim using the trompe-l’oeil (French for “deceives the eye”) technique.

In 1890, the year this watercolor was produced, Hirst began portraying objects associated with male pastimes. Such subject matter had long been the focus of male artists, but where they celebrated activities like hunting and pipe-smoking, Hirst critiqued masculine culture.

Throughout her career, Hirst also included books in her compositions. Many of these texts were by early progressive women writers. Unlike her male counterparts, however, Hirst rendered books with legible pages and illustrations, drawing viewers’ attention to the beliefs that she is thought to have championed as a woman and an artist.

An Interesting Book, 1890. Claude Raguet Hirst (American, 1855 - 1942). Watercolor on paper, 10 x 14 in. Canton Museum of Art

Alice Schille

Considered one of America's foremost women watercolorists, Ohio native Alice Schille earned international recognition for her fine Impressionist and Post Impressionist paintings of street scenes, beaches, markets, and women and children. Graduating from the Columbus Art School (which later became the Columbus College of Art and Design) at the top of her class in 1893, Schille continued her studies in New York and Paris. She was a student and twice an instructor at the Columbus Art School (now the Columbus College of Art and Design), a remarkable achievement for a woman at the turn of the century.

Schille's images are intimate, casual, and cheerful statements, and for the most part unburdened with heavy symbolism. She adapted her style and content to each country she visited as well as different areas of the United States. Her experimentation with various artistic styles lent itself to the area that she painted, giving that location a specific feeling. White Houses, for example, is bathed in bright colors and spotted patches of sunlight, giving the feeling of warmth and energy. As a female artist in a male-domainated world, she signed her work A. Schille to conceal her gender and avoid scrutiny.

Although personally shy, Schille possessed unusual courage and strength of will. These characteristics were reflected in both her independent lifestyle and in her art, as she continually worked to master new modes of painting throughout her career.

White Houses, 1916. Alice Schille (American, 1869 - 1955). Watercolor on paper, 17 x 20 in. Canton Museum of Art Collection, From the

James C. & Barbara J. Koppe Collection, 86.15

Elizabeth Catlett

One of the most influential Black artists of the last century, Catlett’s work explores the intersection of life and art, confronting race, ethnicity, feminism, and motherhood with her unique fusion of modern art and folk art. Catlett was barred from studying at the Carnegie Institute of Technology because of her race, and instead studied at Howard University and the University of Iowa. During the post world war two anti-communist movement, Catlett was investigated for her vocal artistic opposition to racism, sexism, and economic inequality. She moved to Mexico in 1946 and was exiled by America after renouncing her citizenship in 1962.

In Mexico, Catlett became an advocate for workers in her adopted country. She empathetically pictured the evils of poverty, including women and children laborers. The woman in Mother and Child takes on a protective, almost urgent pose. Catlett’s intense interest in the mother and child theme reflects her own history; her father died before her birth, so her mother and maternal grandmother raised her. Although men do appear in her work, most of Catlett’s pieces represent women or mothers and children, because, as she explained, “I am a woman and know how women feel."

Mother and Child, 1945. Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915 - 2012). Lithograph on paper, 8 x 6

in. Canton Museum of Art Collection, Gift of Louis Held, 66.11

Jane Peterson

As a child, Peterson exhibited an early gift for art. Though her talent was unmistakable, her path as an artist was by no means easy. Money was tight and her father was not supportive of the career prospects for a young woman intent on studying art. Nonetheless, she borrowed $300 from her mother to cover railroad fare, tuition, and initial living expenses to move to New York and study art.

Peterson was one of America’s most innovative artists, creating an individual style that blended traditional approaches to painting with the art of the Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, Expressionist, and Fauve movements. Peterson was intrigued by urban and rural American life as well as the great cityscapes of Europe. As a woman, her life was much more independent and adventurous than those of most of her contemporaries, and she traveled widely to paint. In the summer of 1907, Peterson took a trip to Europe, visiting England, Holland, and Italy. Europe offered Peterson the opportunity to visit scenic locales and receive instruction from painters who could further her understanding of technique and use of color.

In 1938 Peterson was named the “most outstanding individual of the year” by the American Historical Society – she was only the second woman to receive this honor.

Crowded Street in Venice, c. 1912. Jane Peterson (American, 1876 - 1965). Gouache on illustration board, 23 x 18 in. Canton Museum of

Art Collection, Purchased in memory of John Hemming Fry, 2009.5

Patti Warashina

Patti Warashina had no intention of becoming an artist. Her Japanese American parents encouraged her and her siblings to take their education seriously and go into a field that guaranteed they would earn a living. Warashina’s father was a dentist, and Patti attended the University of Washington with the intention of becoming a dental hygienist.

Warashina’s studies required that she take a beginning drawing class, which she thoroughly enjoyed, causing her to sign up for more art classes, which led her to clay. She was hooked, but stayed on track to become a dental hygienist. Finally her advisor said, “Patti, just face it. Do it. Transfer over.” She did, and she became so enthralled with clay that she would work in the studio until midnight every night and leave a window open on Fridays so she could sneak back in on the weekends. “That’s how bad it was,” she said, “I was really addicted.”

Warashina crafts figures out of clay that reflect human nature and humor. She has a great interest in the absurdity and eccentric nature of human behavior, and her clay figures become actors in her introspective narratives. She once said that "you’d have to be a masochist to be a ceramic artist,” because it is a difficult material that can crack at any stage, and what happens to it in the kiln can't be controlled.

Warashina has had an exemplary career as one of the rare women in the field and was honored in April 2020 as the Smithsonian Visionary Artist.

Hammer Head, 1987. Patti Warashina (American, b. 1940). Clay, plexi, and wood, Purchased by the Canton Museum of Art, 87.10

Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu was raised in a traditional Japanese household whose values, as well as the surrounding Hawaiian landscape, strongly influenced her work. Her primary medium, and that for which she is best recognized, was ceramics. Today, she is considered one of the finest ceramic artists in the world, and at the forefront of a movement that turned ceramics from a craft into an art form.

Takaezu developed her own distinctive closed-form figures, such as the Tall Floor Vessel pictured above. She had a spontaneous approach to glazing, in which she would walk around the vessel, freely applying glaze through pouring and painting. Her first closed forms were a response to her desire for a continuous surface to glaze. Despite the painted surfaces’ vivid colors and complex compositions, the dark interiors were just as important and intriguing to Takaezu. For her, the enclosed space was a metaphor for the human spirit, or its own micro universe - a place unseen with a powerful and mysterious presence. Takaezu's work was also unique in the fact that she often incorporated sound by placing clay beads in some of her closed pots, which rattle when handled.Takaezu found that the senses of sight, touch, and hearing were closely connected.

Last but by no means least, Takaezu was a profoundly influential teacher and mentor, who trained generations of younger artists at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Princeton University, and other institutions. Her legacy lives on in these students and apprentices, and above all in her own work. Upon establishing her Quakertown, New Jersey studio in 1975, Takaezu began formally mentoring young artists through an immersive, live-in apprenticeship. Today, her home is preserved as the Toshiko Takaezu Studio and continues to be used as a creative workplace by students and artists alike.

Tall Floor Vessel, c. late 90s/early 2000s. Toshiko Takaezu (American, 1922 - 2011). Stoneware, Canton Museum of Art Collection, Gift of

Viola Frey

Best known for her large-scale ceramic sculptures, Oakland artist Viola Frey was a central figure in cracking the barrier between art and craft. Though an integral part of this movement, as a woman Frey struggled to stand out within it and spoke quite candidly about it. Over the course of her five-decade career, Viola Frey created boldly-colored figurative sculptures, paintings, and works on paper that reflect on contemporary culture, power, and gender dynamics. In her work, men wear power suits and women are clothed in traditional 1950s fashions, or in the nude. While living in New York, Frey was first confronted with the multitudes of suited men in the world, and within the art world. She once said "the man in the suit was about power."

Frey was a passionate collector and haunted her local flea markets - buying china, books, figurines and knick-knacks, all of this serving as inspiration for her work. She used a distinctive, personal iconography and palette to depict human figures arrayed among objects of antiquity, flea market collectibles, and interior landscapes. In her piece pictured above, a man in a suit towers above figurines that look inspired by her collected knick knacks - including an Alice in Wonderland. Though this piece is on the smaller scale, Frey created many monumental works, soaring in height to twelve feet, an extraordinary accomplishment in clay.

Untitled, 1995. Viola Frey (American, 1933 - 2004). Ceramic, 22 x 17 x 9 in. Canton Museum of Art Collection, Purchased in honor of

Phyllis Sloane

Phyllis Sloane encountered understandable frustration in the 1950s when family life began to compete with her life as an artist. “All women artists who had children felt guilty," she once said. Though she discarded her hopes for a career in industrial design, Sloane refused to give up her artistic passion. Instead she adapted, forming a sketch group with several artist friends. These early sketches formed the basis for many later prints and paintings.

Sloane gravitated towards representational work and was strongly influenced by the Pop Art movement. She acquired an old printing press that she refurbished, and thus began her life-long love of and experimentation around printmaking. Her body of work consists of a remarkable variety in this field, including etching, silkscreens, lithographs, woodcuts, linocuts, monotypes, enamels on copper, ceramic tiles, and heat transfer prints. Total integration of the figure with its setting became a major theme of a series of opulent silkscreens created in the 1970s, including Cathy in Grey. She was influenced strongly by artists Alex Katz and Will Barnet, who shared her interest in depicting the female figure.

Cathy in Grey, 1979. Phyllis Sloane (American, 1921 - 2009). Silkscreen on paper, 26 x 29 in.

Canton Museum of Art Collection, Purchased in memory of Ralph L. Wilson, 79.27

Mary Spain

Set in a realm of fantasy, Mary Spain’s work depicts oddly distorted figures in a child-like manner, conveying a sense of absurdity. Spain’s interest in antique dolls and toys lends insight into the construction of her figures. Many figures have marionette like qualities with blocky, out of proportion limbs, suggesting that perhaps they are not entirely in control of their actions. Most of her characters are seen wearing odd or unusual hats, such as in Hanging Clown with Yellow Cat. Spain believed that these hats gave her figures identities, much like they do for professions such as chefs, construction workers, or police officers. The hats also serve another purpose - to contain the characters. While her figures often appear cute or innocent, Spain felt they were filled with mischief. Without their hats, she imagined that they might just explode. During her struggle with the cancer that would ultimately claim her life, Spain used these figures to express her feelings of pain and sadness, especially since they portray a lost sense of control.

Hanging Clown with Yellow Cat, c. 1970s. Mary Spain (American, 1934 - 1983). Oil on canvas, 26 x 30 in. Purchased by the Canton